November began and continued with the weather still warm and wet as a series of Atlantic fronts, one after the other, continued to arrive from the south-west. The same conditions had already prevailed pretty well unchanged for several weeks. At first the showers were intermittent and rather unpredictable, but some became really heavy so that by 1st November the summer drought had been truly overcome with all our rivers in proper flood. For this reason alone, there wasn’t too much for grayling fishers to be doing for a while. Salmon anglers, with their season now over, could at least content themselves with the thought of good running conditions for any late fish. Meanwhile the Wye coarse fishers, those who target barbel and chub which hunt by scent rather than sight, were doing rather well in the warm floodwater, although necessarily fishing in slacks or close in to the bank using weights as heavy as 6 ounces. Incidentally, and before I move on to this month’s fishing, those who fish the Usk Reservoir might be interested by the report of MRP from Ammanford from 31st October. Nothing was caught, but he has some interesting things to say about wind direction on this large upland lake.

Fownhope - SL from Aldershot

Fownhope - SL from Aldershot  High water at How Caple Court - GB from Bristol

High water at How Caple Court - GB from Bristol With a very few intervals the floods continued for most of the month. Accordingly I contented myself with hunting for some fry feeding rainbows in our Forest Pool. The signs of fry attack were clear on the shallows at the head of the lake and around the marginal weed beds – little roach in numbers don’t normally jump out of the water for sheer fun. The lunging rainbows which weigh between 2.5 and 5 pounds have of course been stocked, but soon learn to make a living from what is edible in the pool. These days I take a simpler approach than before and don’t often find it necessary to use any particularly accurate fry imitation.

One favoured technique is based on a floating line and a longish leader with a heavily weighted fly such as Charles Jardine’s Moorhen Spider. The heavy tungsten bead on this mainly black lure makes it awkward to cast, but produces a wonderful up and down motion of the tail on the retrieve. On other days a clear intermediate line coupled with anything with a long marabou tail will work better, simply because you can easily experiment with counting down to different depths and of course the trajectory of the lure is different to that with the floating line, Cats Whisker, Humungous or a big Goldhead Damsel all work. With the intermediate line keep the tip of the rod below the surface while retrieving and strip-strike when you feel the line tightening.

Forest Pool B

Forest Pool B  Fry feeder

Fry feeder  Moor Hen Spider B

Moor Hen Spider B  Fry feeder lures

Fry feeder lures The Moorhen Spider, by the way, is a slightly odd pattern, in that it is really a small lure rather than a true spider and there is no particular need that I can see to use moorhen for the hackle. Maybe the name was inspired by the combination of black and red, just like the bird? In the case that you feel like trying it, here is the original dressing with some suggestions:

Hook: Standard wet black nickel in sizes 10, 12, 14

Bead: Black tungsten to match the hook size

Thread: Black or red 14/0

Hackle: Black hen

Tail: 6/8 whispy fibres of black marabou (or thicker if you like)

Rib: Fine red wire

Tag/butt: Red/claret holographic tinsel

Body: Black dyed soft animal fur – muskrat, beaver or rabbit (or plain old seal’s fur; why not?)

It strikes me that the Egg-sucking Leech, another black and red lure, might be a good alternative.

There’s another slightly surprising one which seems to work at this time of year with rainbow trout which are interested in fry. This is the Holographic Dunkeld which is obviously a modern development of a classic pattern. It theoretically mimics a male stickleback in spawning colours, which might or might not fit with this season of the year. Still, tweaked along in a lively fashion on either line, it seems to work. I usually tie it on a low water salmon hook:

Holographic Gold Dunkeld

Holographic Gold Dunkeld Hook: Low water salmon 10 or 12

Thread: Red 8/0

Tail: Golden Pheasant Crest

Rib: Fine oval or gold wire

Body: Holographic gold Mylar

Hackle: Orange hen or Chinese cock

Wing: Bronze mallard

Eyes: Jungle cock, small

By the weekend of 12th/13th November, the rain having eased off for a bit, levels on the upper Wye and some of the tributaries indicated that grayling fishing might now be just about possible and accordingly I hoped there would be some reports for me to read on the Monday. DC from Weyhill with a friend reported 11 grayling while fishing the Severn Arms no 1 beat of the Ithon on the 12th. That’s one to remember; it’s been a while since I fished that part of the Ithon. AC from Minfield with a friend fished the upper Wye at Dolgau on the same day and they had 9 grayling plus a couple of out of season trout. However, a day later SE from Bridgenorth with a friend fished the same beat and found the conditions very difficult: “In my opinion, this is not a viable grayling fishery.” I agree the wading and travelling on this particular beat is more difficult than most, except perhaps for the gravel stretch just above the bridge. A very big current was running on the day in question which must have made the situation intimidating. As SE noted, the upper part with its access boards is primarily organised as a salmon fishery, and historically it was famous as such. Today, salmon on this part of the river tend to be encountered only in the very last weeks of the season, but if you can believe August Grimble’s description, in 1905 they reckoned to catch big springers up here when the season opened in January. Those were the days!

On the 13th also MB from Abergavenny fishing downstream at Abernant had a big catch of grayling to 14 inches on a “pink bug.” Abernant is one beat where you can find places to fish even when the river is high, say 2ft or even higher on the Llanstephan gauge. If the water is clear enough and the level holding steady or falling, you are in with a chance! PT from Kidderminster with a friend had a large catch of grayling and out of season trout from the Lugg at Eyton.

By the weekend of 12th/13th November, the rain having eased off for a bit, levels on the upper Wye and some of the tributaries indicated that grayling fishing might now be just about possible and accordingly I hoped there would be some reports for me to read on the Monday. DC from Weyhill with a friend reported 11 grayling while fishing the Severn Arms no 1 beat of the Ithon on the 12th. That’s one to remember; it’s been a while since I fished that part of the Ithon. AC from Minfield with a friend fished the upper Wye at Dolgau on the same day and they had 9 grayling plus a couple of out of season trout. However, a day later SE from Bridgenorth with a friend fished the same beat and found the conditions very difficult: “In my opinion, this is not a viable grayling fishery.” I agree the wading and travelling on this particular beat is more difficult than most, except perhaps for the gravel stretch just above the bridge. A very big current was running on the day in question which must have made the situation intimidating. As SE noted, the upper part with its access boards is primarily organised as a salmon fishery, and historically it was famous as such. Today, salmon on this part of the river tend to be encountered only in the very last weeks of the season, but if you can believe August Grimble’s description, in 1905 they reckoned to catch big springers up here when the season opened in January. Those were the days!

On the 13th also MB from Abergavenny fishing downstream at Abernant had a big catch of grayling to 14 inches on a “pink bug.” Abernant is one beat where you can find places to fish even when the river is high, say 2ft or even higher on the Llanstephan gauge. If the water is clear enough and the level holding steady or falling, you are in with a chance! PT from Kidderminster with a friend had a large catch of grayling and out of season trout from the Lugg at Eyton.

Abernant grayling - MB from Abergavenny

Abernant grayling - MB from Abergavenny  Lugg grayling in autumn

Lugg grayling in autumn Results from the Irfon for the same weekend were not so good, although the water was clear and the level coming down nicely. On the 12th RS from Nuneaton fishing at Melyn Cildu caught no less than 30 out of season trout and just two grayling. AW from Salisbury fished at Gofynne, first nymphing and then trotting, but could only account for 9 out of season trout. He wondered where the grayling were, being used to bumper catches in previous years. PB from Leicester fished the lower end of Cefnllysgwynne with the trotting rod and had 15 out of season trout, 2 chub and just 4 grayling. However, he was quite happy with this result as one of the grayling was a specimen of 2 pounds, 3 ounces.

I was booked on the same water the following day, unknowingly fished the same pool as PB, and caught just 2 small grayling, but 9 out of season trout of different sizes. Then I had to keep moving because the trout were being so bullish (no sign of spawning yet) and also because of the presence of salmon. I looked up my fishing diary when I got home and saw that in exactly the same area 12 months before I had recorded a good catch of large grayling (fish of 17 and even one of 18 inches), but noted then a concern about the lack of medium or small ones. “Where are the shotts?” I had written in the margin. I also remembered that last year Melyn Cildu and the Colonel’s Water earned themselves a reputation for producing a few specimen grayling, but virtually no smaller ones.

Now taking some time to think this through, it’s the case that grayling, like salmon, are a relatively fast-growing and short-lived fish. They have good spawning seasons and bad ones, the numbers fluctuate as they go through their life cycle, and any given fishing trip might produce a preponderance of a particular size and year class. This I take to be the normal characteristic of grayling populations and “where are the small/medium/large ones” is a complaint we have heard before. A very large number of small ones in the catch one particular year might be followed by a goodly number of medium sized fish, and finally a few large ones before the cycle repeats itself. That would be one theory applicable to the Irfon or any other river. Or in this case maybe the grayling were present in the Irfon but off the take for some reason? Fishing results, rather than electric fishing surveys, are a relatively inaccurate way of determining what exists in a river and grayling are notorious for switching on and off the feed. Another unanswered question is how much damage is being done by summer droughts, which now seem to be coming year after year? When there is little or no rain, the Irfon gets very low indeed. Finally I did wonder if the Irfon, having been affected this November by the first flood after a very long drought, might have experienced one of its notorious acidic flushes arising from the plantations of conifers upstream. If so, this might have temporarily poisoned the water enough to dissuade grayling from feeding, but not the trout? The vulnerability of this beautiful mountain river to acidic water is well known. The WUF for years have undertaken programmes to combat the problem, and it is generally accepted now that the conifer plantations were not a good idea, although the sources have been limed and drainage ditches in the plantations blocked off to slow down the outflow of water. Every time I fish in that valley I look up at the close-packed pines ranked in sinister formations on the skyline above and remember Jon Beer’s description of them: “Like Zulu impis looking down on Rorke’s Drift.” With this threatening image in mind, I have sometimes found myself muttering like Colour-Sergeant Bourne: “Look to your front. Mark your target when it comes.” See also the paragraph below about phosphate measurements taken on the main Wye during these recent November floods. Let’s watch to see how the Irfon fishes later in the winter.

Cefnllysgwynne autumn

Cefnllysgwynne autumn  Arrow grayling

Arrow grayling Returning to our catch reports, there followed more rain showers and again raised flood levels on our rivers so over the next week only barbel and chub fishers had much of a chance. By Friday the 19th high pressure had temporarily returned and the levels dropped somewhat again, so a few grayling fishers were out over the weekend. I had a good morning at Eyton in bright sunshine and with a sharp morning frost over Herefordshire, this being the first proper freeze of the season. The Lugg was running high and fast, but not too coloured and bank fishing was quite practical. NH from Manchester had a good day on the Welsh Dee at the Glyndwr Preserve, catching 10 grayling on nymphs close to hand. This little interlude didn’t last too long and more rain over the weekend quickly increased water levels once more. Everybody, even the barbel fishers, struggled for the rest of the month. SC from Leeds arrived on the bank of the Tees at Coniscliffe, but returned home when confronted with the flood: “H&S ruled out fishing.” RE from Cwmbran parked on “hard standing” at the Wye’s Lower Canon Bridge, and then spent 3 hours extracting the car from the mud. AP from Northstowe with a friend did manage 4 grayling from the Dee at Llangollen Maelor on the 27th. By the end of November the weather seemed to have shifted to a cold, dry, high pressure systems and levels were falling, so that it seemed that there would be some grayling fishing before Christmas.

A new salmon catch total for the Wye arrived in November: 427, the biggest being Brian Skinner’s estimated 30 pound springer from Gromaine. This compares with the 376 recorded at the season’s end on 17th October. It seems some of the lower beats sent in late returns of fish caught during the final month. Well, that’s 50 fish better than we thought, but the situation basically does not alter. Most of the fish were caught below Monmouth and the middle and upper river were starved of salmon. Trevor Hyde who heads the salmon section at Ross Angling (just three fish taken this season) has been taking regular phosphate samples of the river at Weir End and just upstream for the last couple of years. We should be grateful for the work such “citizen scientists” are prepared to put in. During the months of drought, with little or no surface drainage into the system, he regularly recorded nil readings for phosphates in the water, which on the face of it might have seemed extremely encouraging. Ranunculus weed began to recover. However, as soon as the rain began and the river rose, his phosphate tests recorded levels of 13.8, 7.4, 23.3, and finally an astonishing 64.1 times the permitted reading. So much for the theory that high flood water dilutes pollutions to the extent that they are harmless. In this case the obvious conclusion is that the phosphate pollution, presumably spread in slurry, had been collecting and lying out all summer on dry farm land where it would do no harm, but as soon as serious rain began it all arrived in a rush to drain through the streams and rivers.

Upper Hill Court - KT from Bath

Upper Hill Court - KT from Bath During the pandemic period our local clay shooting grounds had to come up with various methods of social distancing, supposedly to keep participants and staff safe. One idea was to do away with shooters going round the sporting course in small groups working the traps themselves and filling in the cards for each other, then moving on to the next stand as the next group showed up. Obviously there were some infection risks in such a happy-go-lucky system although it is an easy way to accommodate large numbers and probably profitable to the shooting schools. Instead shooters under pandemic conditions would go round solo, starting off at 5 minute intervals, each accompanied by one of the staff working the buttons and filling in the card with gloved hands. In one sense I liked it well enough, with plenty of time to concentrate on assessing the flight of clays without any distraction. Every few seconds the world would narrow down to those black or orange discs flying across the sky and the rib and foresight on top of the barrel of the swinging gun. Killed the first bird but missed the second. “Click, click” as two new cartridges go in, call “pull” and repeat, try to do better. The rustle of wind can be heard in the headphones while waiting for the clays to launch, and yet the device cuts the decibels of actual detonation down to not much more than a thump. A round of 50 or 60 birds is over all too soon.

Loaded trap

Loaded trap  Sport for every one

Sport for every one  Taking the shot

Taking the shot On the other hand, we all found we missed the crack of shooting with friends. Shooting is a universal sort of sport, capable of accommodating people of all ages, sexes, abilities, and indeed disabilities. With some forward planning, you can shoot from a wheel chair. A friend of ours has a prosthetic leg and these days finds it quite difficult to get around the course when the going is muddy or steep. However, once in the gate and with a secure footing he shoots like an angel and you can see how he loves it. So the social life is a big part of the clay shooting scene. Just occasionally there is a risk of insensitive “banter” becoming “barracking.” I have seen people distracted and offended by particularly relentless joking, at least if it comes while actually taking the shots. Ernest Hemingway once wrote: “Somebody back of you while you are shooting is as bad as somebody looking over your shoulder while you are writing a letter to your girl.” I never felt irritated to that extent; moreover Papa Hemingway could shoot. At least if the unnerving party trick of shooting lit cigarettes from the mouth of a friend with a fairground rifle is anything to go by, he could shoot. Meanwhile as a novice I still need all the help and advice I can get, always provided it’s well intentioned. Almost everybody shoots better than I do, and a quiet voice behind from someone who has an eye for the fall of shot can often make me correct a mistake and exceed my own expectations. Still, it’s a tricky thing offering advice; and that is also true of fishing. As an angler I have learned to wait until I am asked, lest I give offence.

Now I am going off on a tangent for a moment, but you will see why eventually. The first aircraft my father learned to fly was a De Havilland Tiger Moth and this was accomplished through the auspices of the Oxford University Air Squadron. As far back as the early 1920s, the Royal Air Force established a plan which they hoped would create a flow of air crew into the ranks of their relatively new service. An air squadron would be established at each of the major universities; students would get the chance to learn to fly and those who demonstrated some level of talent would be offered a short service commission after their degree. Initially the project was run on a fairly small scale and in peace time the number of new pilots required each year was relatively small. When World War II broke out the number of aircrew required suddenly increased exponentially, particularly considering the casualty rates being experienced. The university air squadron scheme, which had proved quite successful, was expanded accordingly. Some names which would later be famous went through the system and on into the RAF, including the actor friends Richard Burton and Warren Mitchell. My father would have been just 17 when he went up to Oxford in 1942; he learned to fly in the University Air Squadron and was commissioned into the RAF when he turned 18.

Flight over Oxford

Flight over Oxford  My teenaged father in the middle

My teenaged father in the middle  Who will be first

Who will be first The Tiger Moth biplane, as father used to tell me, was at least a way to learn the very basic mechanics of flying. It was well designed, reliable, had some aerobatic capability and there are quite a few of them still flying today. On the other hand, by the 1940s and in comparison with war planes it was desperately under-powered and very sluggish, even as a basic trainer. “Rather like steering a slow barge,” Dad used to say. “You had to wait for what seemed like seconds for any reaction to the controls.” On another occasion he also described this beginning as rather like teaching somebody to ride a high powered racing motorcycle by starting them off with a moped. The next stage would occur when the new pilots had actually entered the RAF. The advanced trainer was the American Harvard, an all metal monoplane with a powerful Pratt and Whitney radial engine, two stage supercharger, variable pitch propeller and full aerobatic performance. Once you could fly a Harvard properly you were ready to fly a Hurricane or Spitfire and go on to a front line squadron. My father later in life was modest about his flying abilities, but from his papers after he died I have seen his flight skills rating (exceptional) and he was quite quickly promoted and made an instructor. On reflection, I suppose that may well have saved his life. He went out to the flying school established in Rhodesia, and by his account had a lot of fun hiking in the bush, drinking beer and playing cricket as well as flying and teaching.

My father never saw action as it turned out. After leave in the UK, he was sent back out to the Far East, playing bridge in the troop ship all the way down the Red Sea partnered with one Pilot Officer Wedgewood-Benn. When Japan surrendered he was actually in the recaptured Singapore establishing a new training school at Changi Airfield. He was to teach on Harvards and later Chipmunks for the rest of his post war flying career in the RAF Volunteer Reserve. I note from his log-book that for 45 minutes he flew the Gloster Meteor, one of the first jets, while he was doing a post-war PhD at Bristol University.

Going back to that first training stage in the University Air Squadron; the Tiger Moth had one very great disadvantage. The Harvard was equipped with a practice gun, but the Tiger Moth was altogether too flimsy a construction to house even one machine gun. Consider now the shooting skills requirements needed then for a pilot in Fighter Command. Diving at a fixed ground target would have been, I suppose, comparatively straight-forward. You are moving, but the target is not. But to shoot at another aircraft, which might not be a lumbering bomber but an agile fighter, twisting and turning? Both aircraft are moving, constantly changing their positions and angle of travel. In most cases, unless right on the enemy’s tail, it would not have been effective to simply wait until the sights were in line and then press the button. Rather it would be necessary to work out where the enemy is going to be so that he flies into your stream of shot after the button is pressed. This prediction calculation of course is called lead in shooting circles. These fighter pilots needed a skill that probably every farmer who goes out in his field to shoot at pigeons or rabbits knows about. It is said that even in his free hours the maverick Canadian ace George Beurling, who famously fought a Spitfire through the siege of Malta, could not resist sighting with a fore finger and leading through any bird he saw flying across the sky.

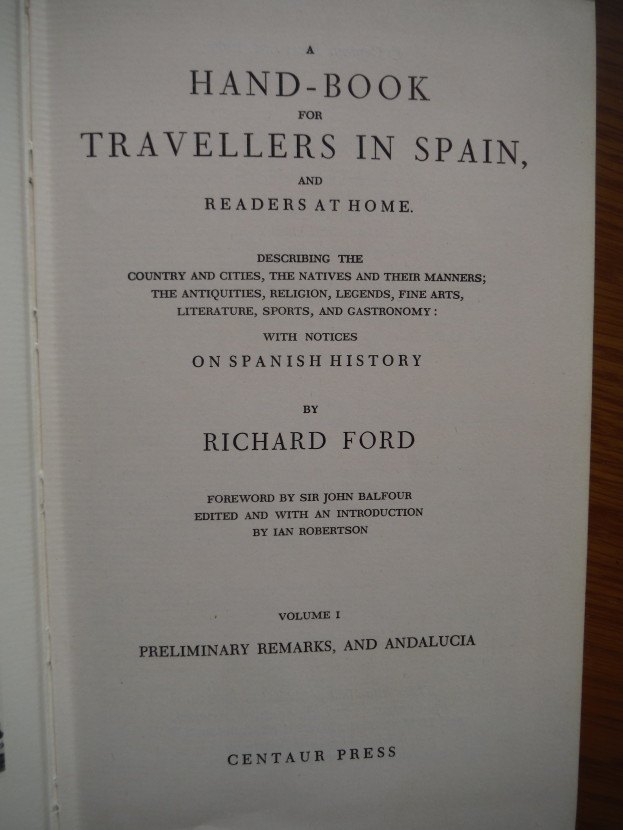

Handbook for Travellers in Spain

Handbook for Travellers in Spain You can see where this is going, can’t you? Did I tell you that as a teenager in the Forest Dad used to wander round shooting rooks? Rook pie wasn’t wasted in the early days of the war. Even I can remember a time when, provided perceived vermin such as grey squirrels and corvids were the target, the Forestry Commission were pretty much free and easy about locals shooting over Forest land. Dad with an old external hammer, side by side 12 bore used to shoot birds for the pot and squirrels for the bounty on the tails. Going back to our University Squadrons and the callow young men learning to fly Tiger Moths, long before the war the top brass of the RAF had discussed how to establish some gunnery practice into the training schedule. “I know what,” somebody said. “Let them shoot some clay targets. That’s what we will do with them and at least they can learn about leading a moving target.” So on Saturdays, quite apart from their training in the air, the student pilots were taken to a sporting estate near Oxford and given a chance to chase clay discs flying across the sky with a shotgun barrel. I rather like the idea of Dad doing that. Later, American waist gunners on the USAAF Flying Fortresses, which bombed by day and were therefore especially vulnerable to German fighters, were given shotgun practice with clays on a skeet shooting course.

Of course lead is largely a matter of timing and together with the movement of the target and/or the shooter (if he happens to be in an aeroplane), there is also the matter of how rapidly the gun and ammunition responds to the shooter’s command. In these days of 1,400 feet per second cartridges, it is pretty rapid, but certainly not instantaneous. In the time of flint locks and muzzle loaders it must have been very much more difficult. Richard Ford, who wrote the impressive Handbook for Spain which made publisher John Murray’s name when it was published in 1845 and has been a source for historians ever since, had this to say about Spanish sportsmen during the 1830s:

“It is wonderful how many of them shoot from nice artillery calculation. They know exactly how long their gun will be going off, and make allowances for its tardy motion, by shooting so much in advance of their object, which unconsciously arrives in time to meet the shot. Francisco, one of the royal gamekeepers at the Coto del Rey, near Seville, with whom we have often been out, killed snap-shots at rabbits, firing apparently at nothing but underwood, yet his gun went off thus, if words can describe it: - he pulled the trigger – the heavy hammer descended – struck the pan – which opened reluctantly – ignition – fizzing – bang, but the process of explosion was completed under a quarter of a minute. Now that detonators are coming in, many shoot quicker than they used, and miss in consequence.”

In an interview with CNN this month, Boris Johnson painted a revealing picture of European disunity in the days immediately before and after the main Russian invasion of Ukraine in February this year. The French were in denial, Macron imagining that he had a special relationship with Putin which would somehow prevent military action. The Germans, and to some extent the Italians, given their dependency on Russian energy, were hoping for a short war and a Russian victory, thus avoiding the need to apply sanctions on Russia and so prejudice their own economy. Some outraged denials, particularly from Germany, have accused Johnson of lying or at least distorting the truth about this period, but his account seems quite plausible to me. Literally over decades some of us have expressed amazement that a nation like Germany, generally regarded as intelligent, would take the strategic decision to allow itself to be dependant for energy on a partner as unreliable and potentially hostile as Russia. Johnson, with advice from the MOD and particularly the British Army, placed his bets on the idea that the Ukraine with western military backing can fight Russia to a stand-still. Other NATO members now seem to be following suit.

So we are where we are. In Ukraine the first snows have fallen and sub-zero winter temperatures have arrived. Slightly to the surprise of Ukrainian forces, the Russians have pulled back across the river from Kherson, blowing the bridges behind them, this being their first major retreat. That might be seen as an attempt to create stabilised winter lines while regrouping takes place, but in fact there are still some active offensives ongoing in Donbas. The Russians have also began a massive missile campaign to destroy Ukrainian infrastructure, particularly the power grid. We have already heard a great deal about the vulnerability of nuclear power stations and dams in these circumstances, but almost everything contributing to quality of modern life depends on the power grid, including pumped water and sewage systems.

This is when wartime life starts to be particularly grim, especially for civilians. I spent quite a few years and particularly winters of my working life without power or water. Offered a choice between the two, I would opt for leaving the water on. In Bosnia we usually had cheaply made wood burning stoves, brought in by UNHCR and other organisations as a humanitarian priority. You can put them in any room and knock out a window for the flue pipe. Everybody was learning by then that the tower block apartments in which many Eastern European people (including Ukrainians) live are particularly unsuited for war. The lifts don’t work and collecting water from low level stand pipes and firewood from trees cut down in the local park becomes a major operation.

During the Gorazde siege, refugees totalling over 30,000 from the Muslim majority villages in that part of Eastern Bosnia were crammed into a small country town for more than three years. At its worst, you had the feeling of being in a cage, with wolves stalking around outside. You could hear the Serb police outside the perimeter talking on short-wave radio. People were living everywhere in the town, even in bus shelters and shop doorways. Conditions rapidly became Dickensian, the walls blackened with soot, the toilets no more than stinking open sewers. A family of 8 to 10 in a small hotel bedroom was quite normal. You would also find those who didn’t possess a stove, not having a soldier or war-widow in the family or not otherwise being regarded by the local social services department as a priority in the corrupt scramble for assets. There was the old people’s home where everybody was lined up in their beds by five o’clock on a winter evening with blankets pulled up to the chin. There was a strong smell of urine in the freezing room and one tiny guttering light had been contrived with a wick made from a piece of string floating in a bowl of oil drained from the axle of a wrecked car. They were sweet old people, particularly anxious not to complain. There was the old Croat woman (one of less than a dozen Croats in the pocket) who had already survived three winters on a pile of rags in a dripping cellar open to the outside. No stove for her. And the prostitute who lived by the river with her deranged adult brother, a girl of 10 and a baby covered in lice in what had once been the toilet of the slaughter house, now a dank, black cave. I will admit that my family had better living conditions with two rented rooms, one doubling as an office, one decent stove, a supply of candles and contact with the outside world via the radio in the car, but Nerma used to go with the other women to wash our clothes in the Drina. Can you imagine yourself wading into the Wye with snow and ice on the banks to do your weekly wash!

I like to think that our deliveries after the convoyed trucks began to come in to our warehouse made life a little more pleasant for the displaced people inside Gorazde although we could not create more space. Particularly bad cases like those above could be helped. And for the “run of the mill” thousands who had been forced from their homes and farms at the beginning of the war, humanitarian organisations could add to their rations and provide medical care by supporting the overworked hospital. We ran some smaller programmes for Serb schoolchildren outside the pocket. We also did what little we could for the terrified Serb minority trapped in their homes inside Gorazde. The real population numbers of domestic and displaced Muslim soldiers and civilians crammed into the pocket was a closely guarded military secret. 70,000 is still claimed by some sources and UNHCR was trying to feed that number, but from the lists created during aid distribution programmes I believe the true figure was significantly less. After the Dayton Agreement, as the roads opened, many Muslims who had been displaced in Gorazde began to leave on buses for Sarajevo where many helped themselves to vacated Serb apartments. We were years sorting out property rights after the war was over. Trials for the war crimes committed by all parties inside and outside the pocket continue even today. However, as with all wars, there is no doubt that most of those who committed such crimes will never face justice. And finally, much of the land around the pocket is yet to be demined.

More than 25 years later we have another European war, larger in scale, but beginning to look very similar in its effects. Even discounting the shelling, whether intensive or sporadic, there will be plenty of misery for civilians. There are as yet few signs of any positive contacts or even any strong international efforts which might lead to a negotiated peace. All the bets still seem to be placed on a complete defeat of Russia. Will this winter of 2022/3 turn out to be no more than the first winter of the Ukrainian War?

Hopefully we will have some grayling fishing during December. Happy Christmas!

Oliver Burch