We started the New Year with record-breaking high temperatures and some of us were wandering around in T-shirts. Not me, though. I leave that sort of thing and especially the wearing of shorts to postmen and women. The public aren’t ready for the sight of my knees. For all that warmth, there were few sights of the sun during the holiday and enough rain continued to keep all the rivers in flood. Topsy-turvy weather and broken records pass almost without notice these days; at the same time parts of Argentina reached 45 degrees while the Great Plains of North America were 20 degrees below normal winter temperatures. It struck me that it’s only in summer that those anglers who day-dream of exotic locations and rivers full of trout would really want to be living in Montana.

Given the ongoing floods, I wasn’t expecting too much from the Christmas holiday reports when they came. This was a matter of people determined to enjoy themselves by getting out there and battling some very difficult high water conditions. IJ from Chipping Norton with a couple of companions turned to the trotting rods while fishing Cefnllysgwynne on the 27th and managed 8 grayling from the margins and slacks. The following day the Irfon was even higher and only one fish was reported. Also on the 27th, JM from Cardiff fished the Dee at Llangollen Maelor and managed 4 grayling on a Pheasant Tail Nymph with a red collar.

Cammarch Hotel grayling - M from Bristol

Cammarch Hotel grayling - M from Bristol  Cefnllysgwynne grayling

Cefnllysgwynne grayling Coarse anglers on the middle and lower swims of the Wye turned up a few chub and barbel, the last doubtless due to the warm conditions. There followed a long gap with more rain and more flooding, the weather being colder now, until on the 7th January JG visiting from Castle Cary reported 4 grayling taken on nymphs at Skenfrith. The Monnow was muddy, but now falling in level. High pressure was taking over now and we had frosts and day-long freezing fogs.

During the cold snap I went grayling fishing with Rob Evans and after one of those excellent heart attack special full English breakfasts (can we still say full English?) at The Drovers’ Tearooms in Builth, we went out to a Wye running very high and cold. Rob, a former Welsh team member, is a famously brave wader and dragged me out to places where I would probably not have gone on my own and certainly not with a client. I don’t want to encourage anybody to undertake anything dangerous but if you must cross fast and deep water, two anglers are safer than one and three anglers are safer than two, provided that you link arms. You do this holding each other’s shoulders, Zorba style, and thus carefully dance your way across the river. You could hold a handkerchief in your free hand, but will probably need it for the rod. It’s been a while since I tried to dance a Cretan pentozali or a Serbian kolo, but it worked out all right this time and nobody drowned. We had a few fish, but the out of season trout seemed in the ascendancy on this occasion and I noticed most had not spawned. For those concerned about salmon redds, I should note with sadness that this year I am not seeing many, nor do there seem to be many kelts or late spawning fish around.

Rob Evans bugging at Builth

Rob Evans bugging at Builth  Irfon at Llangammarch Wells

Irfon at Llangammarch Wells Cold and dry weather predominated as January wore on, mostly without much wind, while the river levels dropped slowly but steadily. These are the conditions grayling fishers like. On the 17th we had news of another big Arrow grayling: PB of Cheltenham reported an 18 inch fish in a bag of 8 taken with the nymph from Tony Norman’s water at the The Leen. On the 19th TL from Abergavenny had 6 grayling to a pound from the Monnow at Skenfrith. At around about this time a report from an angler on the lower river showed a photograph of what looked like a double figure sea trout taken by accident while pike fishing. This has happened before in January and February, but it’s rare. I only wish there were more of them. The outlook for grayling fishing in the final week of January looks good.

The February edition of Fly Fishing and Fly Tying carries a summary of Guy Mawle’s report compiled on behalf of Salmon and Trout Conservation: A dying river? The state of the river Usk. If anybody should know about the state of the Usk over many years, it is Dr Mawle. The report details many of the failings with which we are already familiar in regard to the Wye and has been sent to NRW, the Welsh Minister for Rural Affairs and other official bodies with a complaint that Wales is now even behind England in addressing agricultural pollution and other problems.

Reflections on the Wye salmon season past have not been very cheerful. The latest total figure we have is 328. No doubt that is a minimum figure and a few will have slipped through the net – no, that’s not a joke - but much as it pains me to record it, this is the worst result for a long time. We rarely get accurate figures for the Usk, but results there seem similarly poor. Climate change – and which of us doesn’t believe in that now – seems to be resulting locally in the former British tradition of wet summers and cold, dry winters being replaced by long dry summers and warm winters with massive and extended floods. This new pattern is exactly what we don’t want for salmon either when running or spawning, and for that matter it is not very helpful for trout and grayling fishing. The worst imaginable scenario is that the Atlantic salmon will just move its living quarters further north, much as the runs of Galician Spain and the west coast of France, which were good in living memory, have already faded away.

Grimble - The Salmon Rivers of England and Wales

Grimble - The Salmon Rivers of England and Wales However, I take some very slight encouragement from the knowledge that both our rivers, and the Wye in particular, have been in trouble before and have recovered. The problems were different in those days, but firm action by anglers and fishery owners combined with enlightened legislation bore fruit. A few months ago Barry Paskevas, owner of the Chainbridge beat on the Usk, very kindly sent me a copy of The Salmon Rivers of England and Wales, by Augustus Grimble, originally published by Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner and Co in 1904. “You really should have a look at this one,” Barry said. “There’s a lot about the Usk in it. It tells you just how it was 100 years ago.”

Barry was right. After the initial and inevitable smile about the author’s name and wondering why on earth the Victorian Mr and Mrs Grimble would have decided to saddle their new-born son with a 20 dollar handle like Augustus – and indeed how he subsequently survived his school-days – I had a very interesting read. The copy Barry sent was from the 1913 edition, in itself useful because changes made and occurring in the first decade of the 20th century had been added since the first draft and in some cases the changes were dramatic. In 1913 he was writing: “…look at the wonderful improvements in the Wye, where good management has turned a poor yielding river into the very best in the United Kingdom.” More of that later.

Augustus Grimble had already covered the salmon rivers of Scotland and Ireland and written about deer stalking. In significant parts of the present book, he wrote from personal fishing experience, but in most cases he acted necessarily as a researcher. He covered most of the ground by mailed inquiries as far as I could tell, which must have been laborious. His basic writing technique was to give a geographical description of each river and its catchment, followed by a description of the owners of fishing rights then existing, and then a description of the fishing history and catches, rods and nets, going back roughly 50 years. I need to state that fisheries often change their boundaries and their names as well as their owners, so this is not always easy to follow. I have done my best to relate Grimble’s description to the modern situation with the help of Maude Parker’s map of the Wye fisheries and David Jones’ map of the Usk. Place and pool names and spellings seem to vary at times from those in modern usage; in this article I have usually chosen to follow Grimble’s spelling. Please let me know if you can see where I have gone wrong.

In a few cases Grimble goes back to the 1820s, so the book covers most of the Victorian era of salmon angling and a little of the Hanoverian. A significant date here is the Fisheries Act of 1861 which had already given certain powers against polluters and poachers, established the principle of closed seasons variously for rods and nets, minimum catch sizes, and encouraged the formation of preservation boards by which proprietors might unite to improve their rivers. Once regional fishery boards had been formed, there were generally much better statistical records available. There are nevertheless many examples in the book where Grimble could not obtain good historical catch figures and bemoans the fact, but makes do instead with the number of licences issued by the board to rods and nets respectively. This, logically enough, give at least some idea of the direction of travel in the catch figure.

Overall we have an impression of a gradual progress in the management of salmon rivers from the Georgian period described by William Scrope in Days and Nights of Salmon Fishing on the Tweed, a time when rivers were valued for their netting income and in which rod and line fishing was an occasional amusement for the owners, sometimes rather lawless in its nature at that. This led into a more familiar modern approach when the rod and line sport became more and more valued. Eventually, in many or most cases, the netting was sacrificed to improve the rod fishing. What is noticeable is that in Grimble’s time there were plenty of examples of rivers which had suffered drastic reductions in salmon runs over quite short periods. Such disastrous falls in catch statistics are quite comparable to those which worry us today.

If it is any kind of consolation, our generations are not the first to face these problems and Grimble went on to chart the recovery of many such rivers. The threats to the salmon understood by Grimble are not entirely the same as we have identified now; he discusses in detail weirs and mill dams which blocked fish migration, industrial and mining pollution, poaching, the taking and selling of undersized fish including smolts and, probably more important than every other factor at that time, the widespread and increasingly efficient use of commercial nets removing salmon and sea trout by the thousands, both in salt water and fresh. “Over-netting and pollution are the curse of our English rivers” Grimble wrote, but the idea of farm pollution due to intensive agriculture would have been quite unfamiliar to him. In his day, fishing interests were still working to prevent cities turning raw sewage into rivers, a problem remaining with us even now. Clearly the salmon anglers of every age complain about a drought occurring on more than an occasional year; Grimble in his introduction complains about the “dominant droughts of the nineties.”

Grimble begins his survey with the rivers of the south and I was certainly interested in what he had to say about the Hampshire Avon and other chalk streams, along with the 28 miles of the Cornish River Camel which is where I hooked (and then lost) my first salmon one hot summer day long ago. Although there was a good run of peel, the rods caught only 7 salmon from the Camel in 1902 and I think it was probably a better river in the sixties when I knew it!

He next comes to the rivers of the Bristol Channel in which we are all naturally interested, beginning with the great Severn. This is a strange case in that it once sustained a massive netting industry, but the rod catch has always been comparatively small. Roman Sabrina is usually described as Britain’s longest river although Grimble made it the second and 185 miles, measuring from the source to what he described as Bello Pool, 10 miles below Gloucester, which is supposedly where the estuary begins. I know nothing of Bello Pool, but Grimble may have intended Gloucestershire’s little harbour of Bullo Pill, below Newnham, which used to export Forest coal and stone and before Beeching’s time had a railway connection. Normally the total length of the Severn is described as 220 miles and it is tidal up to Tewkesbury.

The problem with the Severn as a salmon river is that it lacks really good spawning tributaries, the Teme being an exception, and also that the cities along its banks, Shrewsbury, Worcester, Tewkesbury, Gloucester, historically and even recently caused a huge amount of pollution. The addition of 19th century navigation weirs, such as the famous Diglis at Worcester, added to the problems for running salmon. Most of the netting was done in the estuary, although fresh water nets were once regularly set as far upstream as Shrewsbury, but in some years the imbalance of catch figures was extraordinary. In 1869, 50 tons of salmon were netted, but only 50 salmon recorded for the rods. In 1872, 6,500 salmon were netted, for just 12 salmon to the rods. In 1888, 29,475 were netted and 24 to the rods. Grimble calculated that the nets were taking on average 261 salmon for each one taken by a rod and line. So compared to the Wye and Usk, much smaller rivers in volume sharing the same estuary, the Severn has always had a comparatively small rod catch. Severn salmon fisheries are a bit short on fly water, as for most of its length the river is typified by steep muddy banks above water too deep to wade. Much Severn rod fishing was therefore done with spinners or baits and by concentrating on the weirs. Meanwhile proprietors on the upper river were not particularly enthusiastic about improving access for spawning salmon which they believed would spoil their own trout and grayling fishing “just for the sake of netsmen on the estuary.”

Severn estuary

Severn estuary  Lave netting

Lave netting  Tidal Wye at Lancaut; the stone for Avonmouth docks was quarried from those cliffs.

Tidal Wye at Lancaut; the stone for Avonmouth docks was quarried from those cliffs. Grimble describes Severn estuary netting in detail, beginning with the cone-shaped putcher baskets which until a few years ago were made from woven osiers and stood in ranks to catch fish dropping back with the ebb tide. Both sides of the estuary were once lined by these ranks. The design is age-old; 12th century baskets have been found preserved by the mud and they look much the same. Modern putchers are of wire mesh, but even those now lie abandoned in the grass. You can see a big collection of them by the sea wall on Lydney Park’s Tack, where the last putcher rank fishery was dismantled. Putts were apparently a 3 basket trap system, also fixed in position. I can’t recall those, but I do remember the stop nets which were set between two heavy pulling boats staked into the estuary sands. A few lave netters, which are known as “haaf” netters in northern estuaries, still go out occasionally onto the sands, I believe now on a catch and release basis. This is done today purely for the sake of tradition, and catch and release truly seems like a nonsense to me as the tradition involved is one of commercial fishing for food. The estuary has also suffered from pollution since Grimble’s time. There was a time when the bars of our local pubs, along with those notorious pickled eggs, used to display piles of little jars marked “Severn-side Mussels” and “Severn-side Cockles” preserved in brine and to be eaten with a fork, these being the sort of strong flavoured snacks which seem like a good idea round about the fourth or fifth pint of beer. Somebody must have been making a living from cockling. Shell fishing came to a stop when mercury and other heavy metals were detected in the mud and I think the chemical industry, which used to put out a dirty yellow plume of sulphur smoke at Avonmouth, was blamed at the time. The upper Severn was once a coracle river, as was the neighbouring Usk along with most of the Welsh rivers further west; sturdier wooden boats were needed for the estuary tides but only a few of these remain, now laid up and rotting on the banks. Most of the commercial fishing was over by the time the first M4 crossing was built and today what was once together with dairy-farming and cider making the major industry of Severn-side towns and villages, has just about reached its end. What is left is just the rod fishing, confined to a relatively modest few hundred fish a year.

Taking the two editions of his book together, Grimble has a better story to tell about the 147 miles of the Wye. The river has certainly had its ups and its downs, but compared to the Severn there were significant advantages: almost no weirs, the first serious obstruction above the sea being right up at Rhayader; and (historically at least) very little pollution, the only major settlement being Hereford. Without doubt it was a big fish river, even into the tributaries. Grimble tells of Charles Woosnam of the Hendre, who in August 1903 had just taken a 35 pounder from the Irfon (probably at his own water of Cefnllysgwynne) although in fact a 45 pounder had been taken from the Irfon tributary during the 1880s. The Irfon still has a run of the larger salmon, although very late in the year.

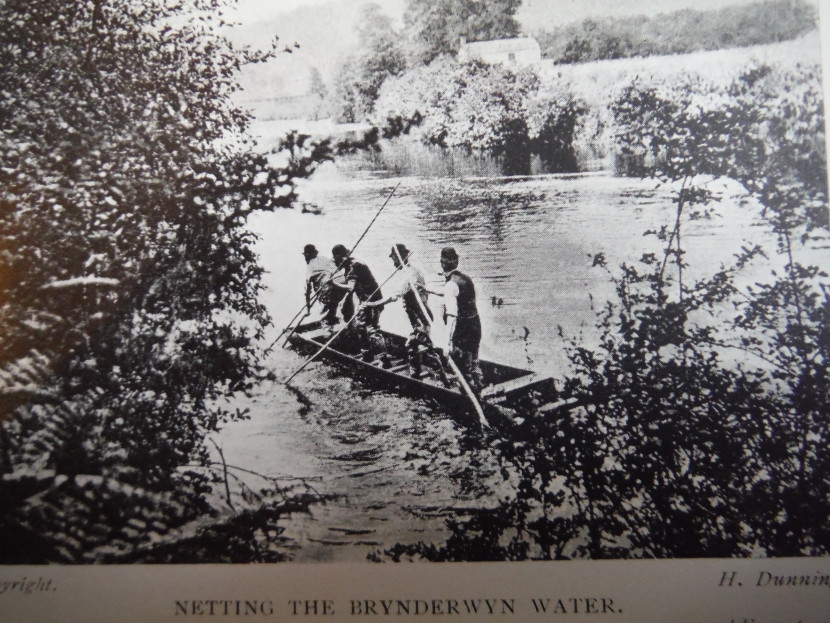

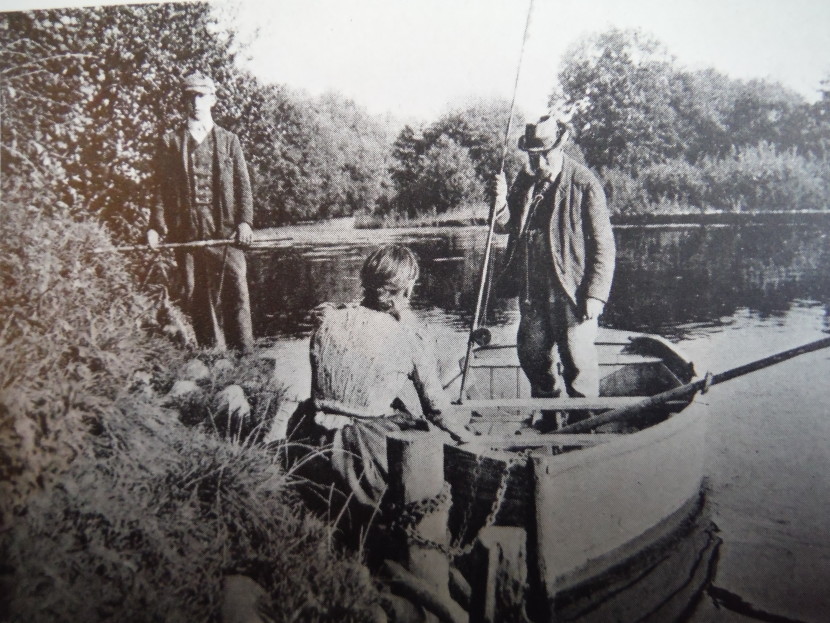

Netting at Brynderwyn and everybody wears a bowler hat

Netting at Brynderwyn and everybody wears a bowler hat  On the gaff

On the gaff The Ithon tributary in those days had a better reputation than it has today. Grimble takes up the story of the Wye in 1860 when it was suffering badly from over-netting and illegal fishing. Kelts were commonly taken from the upper river and sold during the early spring, while he estimates that 200 rod and line fishers were actively fishing the smolt run between Hereford and Monmouth. These were sold in the hotels as “Wye whitebait.” In 1861 came the Fisheries Act, which proved to be the saviour of many a river, and in 1862 the Duke of Beaufort, who owned most of the lower netting rights, donated 300 pounds for the protection of the river and for a war on poaching. 300 pounds went a long way in 1862 and 40 bailiffs were employed. In 1863 an immediate improvement was seen in the number of fish on the spawning beds, but within a year there was already a corresponding increase in putchers and nets deployed on the lower river. A Board of Conservators was formed in 1865 and in 1867 169 rod licences were issued at 20 shillings each. However, the grilse run through the river was now reduced and upper river proprietors complained that improvements in spawning were benefitting the lower river netting interests, but not themselves. In 1869 the owners of a lead mine near the source were persuaded to construct settling tanks to eliminate pollution. A first attempt to provide fish passes on the weirs of the Monnow was made. This is a problem still not entirely resolved; few enough salmon make it into the Monnow to this day.

Upper Wye

Upper Wye By 1874, with 154 rod licences taken out, there was no real overall improvement in the Wye salmon run, and the cause was still believed to be the level of netting undertaken in the lower river. The matter had obviously become quite politicised by this stage and while the lessees of netting rights refused to give information about their catch, it was estimated that they had taken around 12,000 fish that year. In those days, commercial netting would have been active on the river at least as far up as Whitney Court, or practically to the Welsh border. In 1878 there was reported to be a great resurgence of poaching on the spawning beds. The story of the rest of the 19th century is a sad one. Numbers of rod licences taken out did not increase, which is an indication that the fishing was not getting any better. Diseased fish were noted during several seasons. Everybody was suffering now, including the netters. In 1900 the owner of the draught netting station at Goodrich Court gave a statement of his annual catch for the last 9 years, which had reduced from 366 to 46 salmon. He had decided to withdraw his net in future, as the sales of fish were not worth the labour costs.

However, the average weight of fish had increased. Grilse were now rare, but 18 pounders were common. This is interesting and may lend some credence to veteran lower Wye angler Maurice Hudson’s recently expressed theory on the subject. The in-river nets were by all accounts very efficient. Last year with a client I fished a place known as Old Netting Station on the tideway at Llandogo, part of the Bigsweir Fishery. The river runs fast and narrow at this point when the tide is out; I thought I could see the remains of large stakes at the side of the river to make tackle fast and by all accounts there was some sort of crane or hoist to pull up the net and/or the catch. According to Maurice, when in place the nets would have necessarily have been raised during high water (spring and autumn) to prevent damage from debris, but would have fished continuously during low water (summer). Thus the same nets would have taken most of the grilse and two sea winter salmon, while the big three sea winter fish which tend to run early and late would often have had a chance to get through. The reasoning for the increase in size is simple enough, that if you increase your breeding stock of large fish on the redds, you are likely to get large fish also from their progeny.

During 1903, the year of Grimble’s first edition, with the financial help of the Duke of Beaufort and goodwill from the Crown Estates, Wye netting was stopped from Chepstow Bridge all the way up to Hereford. This was mainly the considerable achievement of J. Hotchkis, Chairman of the Wye Fisheries Association founded in 1902 and of the fishery owners themselves. J. Arthur Hutton’s Wye Salmon and Other Fish tells the story in detail. Such co-operation was something of a miracle and accordingly there were great hopes already for 1904. In Grimble’s second edition of 1913, the writer is positively jubilant. The changes had worked and the Wye had now become the best salmon fishing river in the whole of the United Kingdom, he claimed! 635 had been taken by the rods in 1905, but 2,715 in 1910. 1,000 fish averaging 20 pounds had been taken in April alone of 1912.

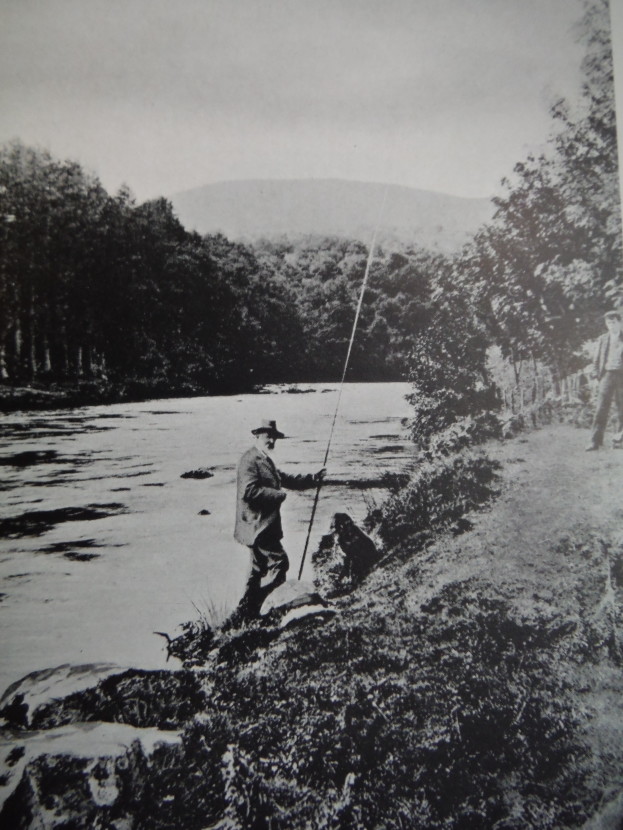

Colonel Sandeman with a long salmon rod

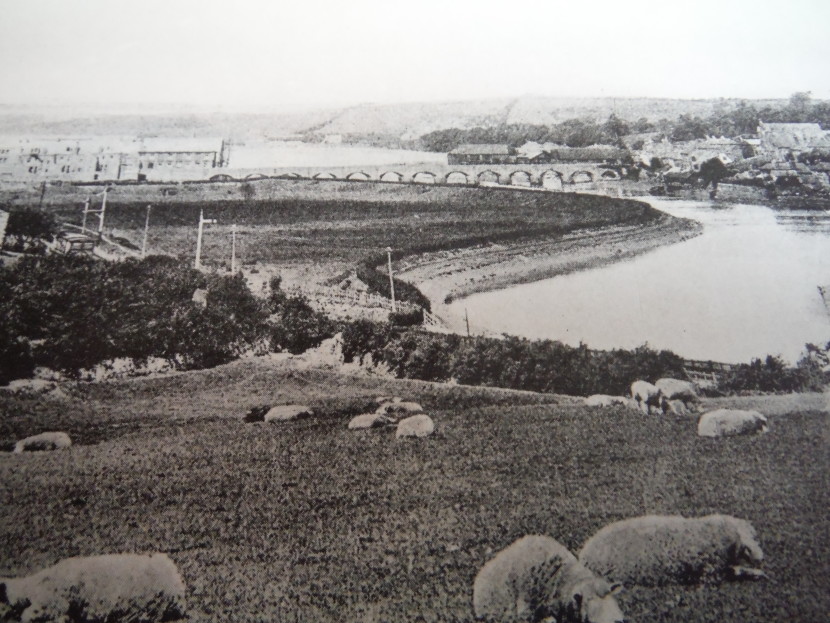

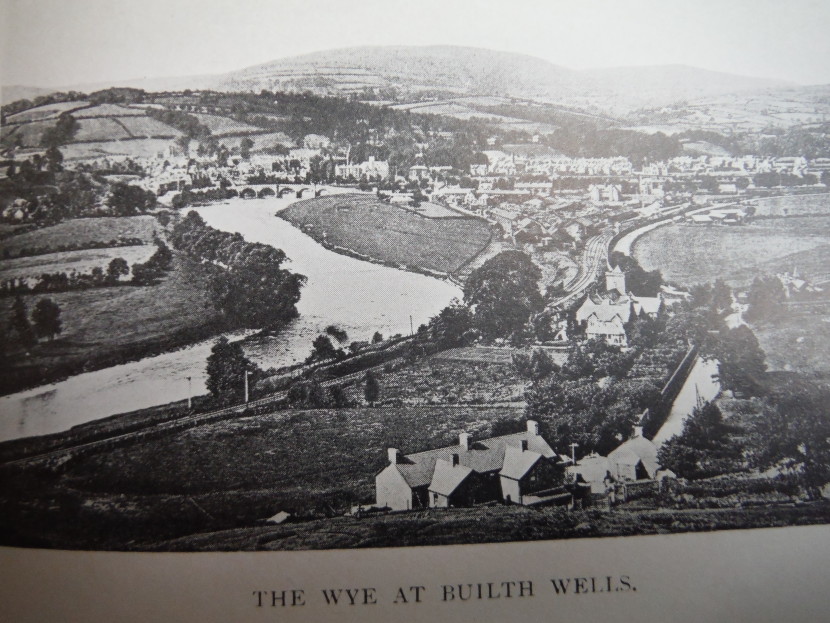

Colonel Sandeman with a long salmon rod  Above Builth

Above Builth  Builth Wells in 1905

Builth Wells in 1905 Grimble starts his detailed description of the Wye fishing at Llanwrthyl Bridge on the upper river. Today it seems quite a wonderful thing that springers could be found as high up so early as March, but thus it is recorded and the springers averaged 20 pounds. Grimble recommends 16 to 18 foot rods for the whole of the Wye, a 2/0 Britannia fly in heavy water, but otherwise Silver Doctor, Jock Scott or Thunder and Lightning. There is one of those intriguing references to earlier patterns: “…old native flies with their long hackles and strips of turkey wing.” He does give a dressing for the Doldowlod Fly, “sombre, weird-looking,” in which badger fur plays a major part. As in most cases, the years have resulted in rearrangements of estates and beat boundaries, but Grimble deals at some length with Doldowlod, Glanrhos and Llysdinam. What is referred to as Doldowlod Common Water is I think what we now know as Craig Llyn; here he recommends the Ash Tree Pool, still well regarded today. Several of his photographs certainly look like Craig Llyn. The subject of large brown trout comes up in this description: “…bull trout have appeared in the spring of 1903…not welcome visitors in a salmon river.” I would suggest that these trout had not appeared from anywhere, nor were they visitors. It is simply that they hadn’t been caught before. They probably would, of course, have eaten parr – what doesn’t? Brown trout even up to double figures are still very occasionally caught from Craig Llyn and other places high up our rivers. Having spent three days early last season salmon spinning on the lower Wye (local lock-down sport) for the slightly unexpected result of a 20 inch trout and a 22 inch trout, I can imagine how these stories came about. He writes of Gallynon’s Pool, which was then part of the Caer Beris beat, later Rhosferig. On the 23rd May 1894, Captain Harcourt Wood using a Jock Scott in Gallynon’s had taken salmon of 31, 27, 21.5, 18 and 15.5 pounds, which gives an average of 22.5 pounds. Grimble tells a tale of Llysdinam involving one Mr William Tayleur who was trying to gaff a big fish when it pulled him head over heels into 20 feet of water. Rather confusingly Grimble puts the scene of this adventure as the junction pool with the “Irwen” which might indicate the Irfon Junction Pool at Builth Wells, but I think it was the Ithon Junction Pool and the place known as Aber Deep which he meant to describe for this accident.

Below Builth Wells of course the river becomes a large one with pools, as Grimble noted, which stay in condition for many days. So we come to what he calls “the pick of the Wye fishing,” or “the splendid 12 miles of the Maeswllch Castle waters belonging to Captain Walter de Winton.” Prior to 1903, more salmon were caught in this section than the rest of the river combined. Really? Today we tend to think of Maeswllch as a modest beat below Glasbury Bridge – I have fished it myself on a WUF ticket - but 120 years ago the Maeswllch Castle estate included almost everything from Aberedw to Hay. Captain de Winton had sublet much of it, but he also fished a great deal of it himself and did very well indeed. Some beat names have changed: Chapel House is still there, but Ponshony (Pontsioni) is now the upper part of Abernant, or Abernant Stream; Tercelyn then included Orchard Catch, now part of Abernant and known as Lady Alexander Catch; Yniswye has become divided between the Nyth and (since 1921) Pwll y Faedda; Erwood Hall and part of the Skreen were roughly equivalent to the modern Ty Newydd; while Gwernyfed Park was equivalent to the modern Spreadeagle. There are some other references which I cannot identify. Lord Glanusk, later to buy Pwll y Faedda and build a house on it, already had some fishing interests in the area.

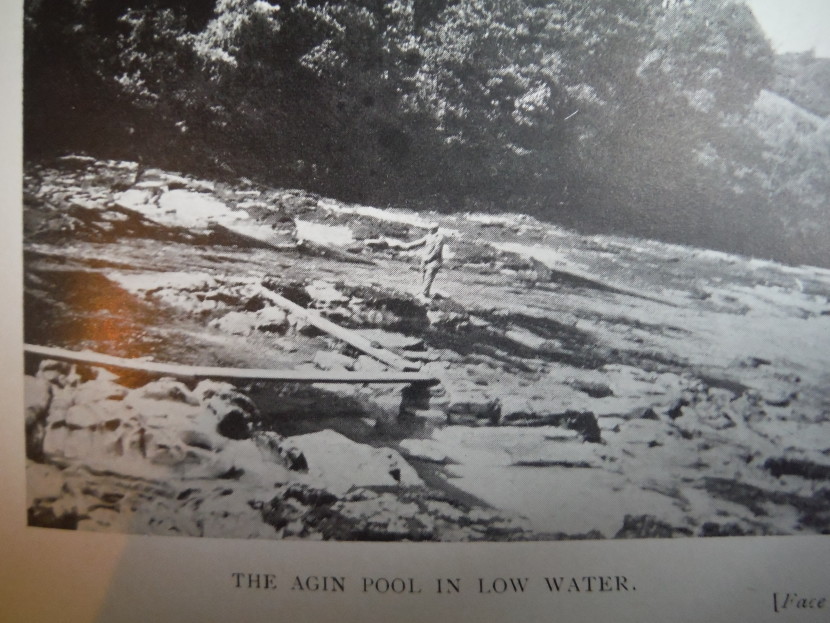

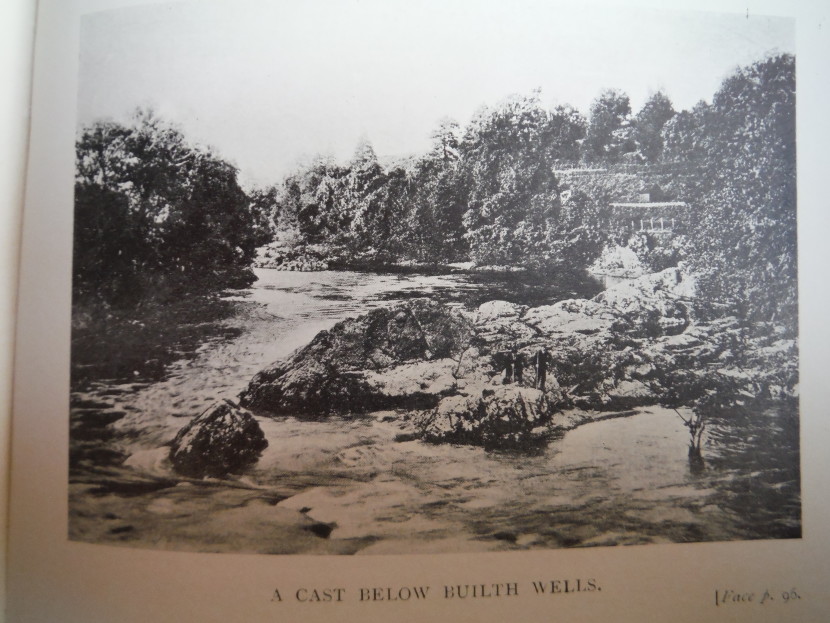

Agin, now part of Nyth and Tercelyn - notes the access planks

Agin, now part of Nyth and Tercelyn - notes the access planks  Below Builth Wells - looks like the Heirag at Gromaine

Below Builth Wells - looks like the Heirag at Gromaine  Wye at Glasbury

Wye at Glasbury Grimble waxes particularly eloquent about the Nyth and cites one Mr W Hartopp who in the first week of April 1903 had four fish in one day from the Cafan Pool: 32, 30, 20 and 15 pounds. Grimble was not the last to remark that this part of the Wye, powerful, rocky and wild as it is, compares well with anything to be seen in Scotland or Ireland. “The best of the Nyth pools are James Catch, Cefn Shon, Lewis, Never-say-die, Agin, Jack Dunn, The General’s, Pull y vadd and Isaacson; the cream of the season is from the middle of April to the end of June for spring fish, for grilse from middle of July to middle of September, with September for autumn fish.” The book includes a photograph of the Nyth’s Agin Pool, which clearly shows the system of walk planks which were bolted across the rocks to aid the angler. When Brian Skinner and I used to fish at Pwll y Faedda, such planks or the remains of them could still be seen in many places, along with the bolt rings which were used to tether boats to let them down the pool. Of the major pools in the modern Pwll y Faedda’s half mile, the Boat Pool and Isaacson’s were perhaps the most exciting ones. I also have vivid memories of a big fish lost in the Jackpot, which used to be called Casino, and of course casting and sometimes catching in the House Pool right in front of Lord Glanusk’s magnificent Arts and Craft lodge which was built between 1921 and 1928. You could literally walk down from the French windows and make a cast. Llanstephan below was in the care of the fortunate Captain de Winton and Maeswllch Castle also controlled Boughrood (the Rectory) and below it Adams Catch (which I think must now be part of Spreadeagle). Adams Catch was apparently famous for 40 pounders. Well-known flies of the day were Jock Scott, Childers, Wilkinson, Dunt, Dusty Miller, Ackroyd, Nova Scotia and Blue Monkey.

Fish Pool

Fish Pool  Wyecliffe near Hay

Wyecliffe near Hay .JPG?w=830) The Bittern, Builth Wells (Francis Francis from local keeper)

The Bittern, Builth Wells (Francis Francis from local keeper) Grimble deals fairly quickly with the Hay down to Hereford section, mentioning Clyro, Whitney Court, Letton Court, Moccas and Belmont. Turner’s Boat, Coxcomb, Monk’s Hole, Deep Well, Starford and Scaur are pools which earn particular mention at Moccas. Mar Lodge, Childers, Jock Scott, Popham and “the old Wye patterns” were the flies in favour. However, this has always been a part of the river famous for its springers and when, as was the case in 1903, springers are in short supply, it suffers accordingly. Moccas was known as a low water beat and only managed 3 or 4 fish that year. This tendency of the middle beats to suffer when springers are scarce is with us again today.

Below Hereford there is mention of Rotherwas and Hampton Bishop, which was already famous as the fishery of the scale reading pioneer J Arthur Hutton who had taken a number of 30 and 40 pound fish from the Carrots. Again these were known as spring waters. Flies were Thunder and Lightning, an Irish one named The Coiner, Silver Grey, Jock Scott, Butcher and Ackroyd. All kinds of baits were used, including prawn, sand-eel and gudgeon, along with Phantoms and a small aluminium minnow made by Hatton Bros of Hereford which, being light, could be spun “…deeply and slowly without hooking the bed of the river as so many of the heavy Devons often do.” Home Lacey and Fownhope, Brockhampton and Ballingham, along with Ingestone and Caradoc, were already well-established estates and fisheries. Aramstone with its Gold Mine and line of battleship islands was in the hands of the Wyndham Smith family, but it seems news of the famous brace comprising 51 and 44 pounders taken from the Quarry Pool within half an hour of each other on a spun minnow failed to catch the second edition. The Ross section, Grimble remarked, contained many pools which due to steep banks and deep water could only be fished from boats. A long, flat-bottomed punt was advised to be the best type. Then came fisheries such as Hill Court, Goodrich Court, Bishop’s Wood and Courtfield, which are still on the map today, but the boundaries and pools covered by each named estate have changed over the years. Goodrich Court then involved the right bank, difficult to fish now, while Hill Court was on the opposite side. The Vanstone and Dog Hole, very well-known catches today, get an honourable mention as the best of that water. The famous Robert Pashley was no more than a young fellow then, fishing the Hill Court waters but yet to make his salmon fishing reputation on these banks. Courtfield was also much larger then than now, included both banks and Park and Monument pools are especially mentioned. Amazingly, Grimble’s account of the Wye fisheries stops at Courtfield, leaving out Symonds Yat which was certainly active at the time. There is no mention at all of anything below Monmouth, which is today normally the most productive part of the river in terms of catch numbers, although water levels play a part in this. So we have a situation where 120 years ago the majority of the fish were taken by the upper river rods between Builth and Glasbury, and now it is usually the opposite, because the majority are taken between Monmouth and the tide except during a very wet season. The answer may be, simply enough, that netting below Monmouth in Grimble’s time was too intensive to allow of much rod fishing to exploit the run.

Grimble has plenty to say about the Usk, a smaller river of 77 miles, because he fished this one regularly himself over many years. Apparently before 1842 the fishing mill weir at Trostrey formed an absolute block to the salmon run. A small consortium of around 20 anglers based on Usk town rented the fishery for 30 pounds, modified the weir to allow some fish through, fished the stretch below themselves and sublet the netting lower down in an attempt to pay the rental. This was an entirely local affair and goes some way to explain why the salmon fishing – not the trout fishing – on the Usk Town Water remains in a very few hands. The Usk Angling Association was formed in 1846, but struggled against the depredations of poachers until given new encouragement by the 1861 Fisheries Act. By 1862 a new United Usk Angling Association had Lord Llanover as its chairman and 120 members each paying a fee of 10 pounds per year – a lot of money for the time. A Board of Conservators, empowered to issue licences at 20 shillings, or 1 shilling for trout, was formed in 1865. There followed a wonderful year; no less than 3,000 salmon including some above Brecon were taken by the rods in 1866 and some individual anglers had over 100. In 1867, which was a dry year, the nets took around 2,000 fish and the rods about 1,000. Disagreements between netting interests and the rods characterised the next period, but Trostrey weir was further opened. There were concerns about industrial pollution from some of the tributaries. Also, for the first time, discussions began with the Canal Company about their right to take unlimited amounts of water from the river at Brecon. Grimble remarked that this was a problem which was never satisfactorily settled in his time and many would say it is not settled yet!

Crossing the Usk at Trostrey Weir

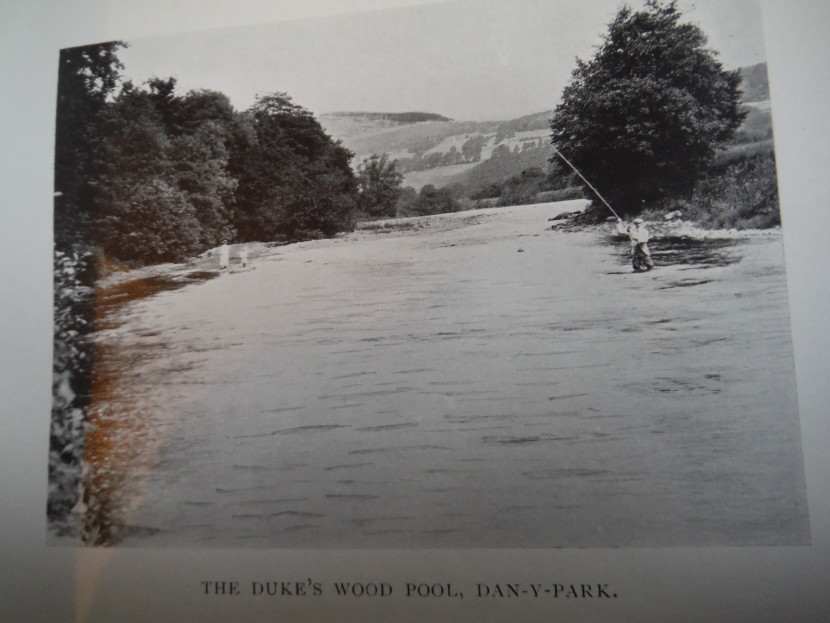

Crossing the Usk at Trostrey Weir  Duke's Wood Pool, Dan y Parc

Duke's Wood Pool, Dan y Parc Grimble then gives catch figures for every year following up to 1903, a time when he himself was closely engaged in fishing the Usk. These are not worth repeating in full, but vary from a wonderful 4,931 fish to the rods in 1891 to as few as 198 in 1901 (a dry year). The Usk was a good salmon river by any standards, but much depended on the rainfall. By this time the United Usk Fishery Association, had acquired about 20 miles of fishing, divided into a lower section, going almost up to Abergavenny and eventually an upper section with more fishing above Brecon. Grimble reproduces all the Association’s rules, which are slightly idiosyncratic: special concessions for the rights of Mr Hanbury on the Crown Fisheries and the Marquis of Bute on Monkswood; anglers divided into classes A, B, C and D. “Except by special order of the Committee, no angling is allowed before 8 am. In the event of two or more salmon anglers being at a catch at 8 am they shall draw lots for the first turn, unless one of them had the first fishing of that catch on the previous fishing day, in which case he shall give way.” Salmon season tickets for the lower water were now 42 pounds. On the other hand, a trout season ticket for what looks like the Usk Town section today was just 5 shillings. No selling of fish. No dogs and no fishing on Sunday. Grimble provides a photograph of the Bell Pool in Usk Town, which looks pretty much as it does now, if slightly more open.

Grimble can’t resist having a dig at the Association’s rule of fly fishing only for salmon, recounting a holiday with friends he spent in 1869 at The Three Salmons hotel in Usk. The fishing was awful; although the river was full of fish, the water was low and nobody could buy a take, despite the use of flies, minnows, worms etc. After about 10 days with nothing caught, one of the party, without telling the others, quietly sends a wire for a parcel of shrimps. Owing to confusion at the hotel when the parcel is delivered, it is sent to the kitchen where the cook arranges them on a dish for the breakfast table. Grimble is down first and enthusiastically eats about half of them before his horrified friend arrives to explain their intended use. They go to the river with what remains and, to cut a long story short, catch a dozen salmon. More shrimps arrive the following day and by this time every angler staying at the hotel wants a share. They are just arranging amongst themselves which pools to fish when another wire arrives from the Committee of the Association to say that shrimp fishing had been prohibited at a meeting held the day previously. Thirty odd years later, this experience obviously still rankles with Grimble who argues that any legal method or bait is fair in such circumstances.

As with the Wye, Grimble gives an explanation of the Usk beats and owners, apart from the Association, beginning at the top: “…the first August or September flood takes the fish to Brecon and beyond.” Grimble also mentioned that sea trout from 2 to 8 pounds run into these upper waters and these are still encountered today on occasions. Beat names and boundaries have changed, but I think Pentreallog might be modern Pantyscallog and modern Cwm Wysg Ganol is mentioned along with Farm and Quarry pools, then Abercamlais, which has changed its boundaries. Penpont then belonged to a Miss Williams and he mentions that John Hotchkis, enterprising chairman of the Wye Board of Conservators, had two days a week there. Modern Fenni Fach does not seem to be mentioned. At Brecon much water was rented by the Association, then came Dinas, rented by the Association from the Lloyd family. Unfortunately I cannot recognise the pool names mentioned. Then came Peterstone, which was owned by Lord Glanusk, Skethrog and Buckland. Grimble has high praise for the trout fishing in this middle section and with justification. He mentions Alfred Crawshay as fishing here; I think this must be the inventor of Crawshay’s Olive, a wet fly I still use for trout. I believe the same Captain Alfred Crawshay was eventually killed in an early flying accident. Some changes have occurred in the next few miles, which we now know as Glan yr Afon, Worcester Cottages, Green Drive etc, all of them famous beats. The Duke of Beaufort then owned water in this section, while Lord Glanusk apparently owned what is now the Gliffaes Hotel water. Next, of course, came the great Glanusk Park water, much as today, running most of the way to Crickhowell. Many of us know the beautiful Park, and any angler still has an opportunity to know it with tickets available from the Foundation. I believe some of the film Tarka the Otter was shot there.

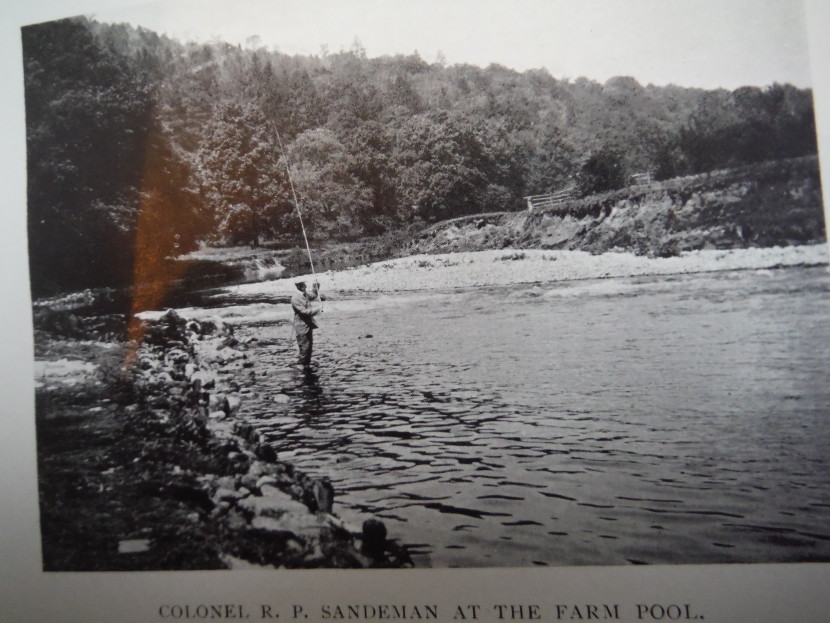

This was followed by the Dan y Parc fishery which belonged to Colonel Robert Sandemann. Grimble goes on to spend nearly two pages extolling the virtues and beauties of the Dan y Parc sporting estate, “one of the best, if not the best, on the river,” along with the daring and impressive exploits of its owner. Colonel Sandemann was apparently: “a hard man in sporting parlance only, ready at brief notice to ride steeplechases, hunt otters, catch salmon, trout and poachers, or to use his rifle at a Bisley long range target or on highland stags, quick and certain with his gun, and equally at home whether searching for a water-ouzel’s nest in the river bank, or dangling over a cliff in mid-air to take a raven’s nest, for some of these birds of unfrequented solitudes build within a few miles of Dan-y-Park.” There is more of this, much more: “On 3rd October 1892, Colonel Sandemann killed with the fly and gaffed for himself twenty-two fish, weighing 236 pounds, the heaviest 22 pounds; they were rising well and hardly one was lost. On the day previous he had eight fish, averaging 11.5 pounds, and on the 4th, another six of 12 pounds mean weight; on the 5th, thirteen others of 12 pounds, and on the 6th, he and his guests killed 1009 rabbits in the Park, and on the 8th Colonel Sandemann rode at Kempton Park.” Once back at Dan y Parc, we learn that the gallant colonel killed another 59 salmon before the season ended.

Coed y Prior

Coed y Prior  Dedication

Dedication In short, Grimble wastes no opportunity to butter up Colonel Sandemann shamelessly. He had good reason to do so; he was a regular guest at Dan y Parc and nobody wants to get the wrong side of a generous host. Free fishing is free fishing. All the same, Colonel Sandemann does sound rather exhausting to be around. Below Abergavenny, Grimble’s list of fisheries and owners takes the form of a diagram showing left and right banks. The town of Abergavenny already has a Corporation Water, followed by Race Course, Clytha, and Llanover with the famous Lady Pool of course. It would have been nice to learn something about the fishing on Barry Paraskevas’ modern Chainbridge water in those days, but I have to rely on the diagram to gather that it must have been shared between Pantygoitre on one bank and Brynderwyn on the other. There is a note about a Colonel Morris who had a five salmon day at Brynderwyn including one of 46.5 pounds. Grimble must have come under some American influence when he called this fish a “sockdolager” and he thought it was the record for the river at the time. Those were the days! I wonder if the big fish came out of the Rock Pool, which still holds good ones, as Barry will tell you. It’s rare on a summer evening not to see a big one moving once at least in this deep pool just before dusk falls. Everything below was Usk Association water, including the Kemeys Commander beat, which I still fish on the Merthyr Tydfil AA ticket.

Grimble had nothing but sad things to write about the rivers lying beyond the Usk to the west. He lists them all, as far as the Towy, and describes them as for the most part worthless. Many were actually fishless, due to industrial pollution from “…the vast and ever-increasing industries of this part of South Wales. The poison refuse of copper, lead, tin, iron and coal works has gained too much ground to be interfered with now, and it is nearly certain that salmonidae will never again frequent any of these streams.” He had this to say about the Loughor, which “…flowing into the Burry inlet of Carmarthen Bay, is sixteen miles in length, with a drainage area of one hundred and fifty-six square miles; it suffers greatly from the pollutions of coal, copper and iron, which are so bad that the river is only preserved in a few places. Fifty or sixty years ago this river was famous for its very large sea trout, many of them scaling from 10 to 14 pounds; then in the early sixties the river was desperately poached all the year round, and though attempts were made to form angling clubs, every effort in that direction was doomed to fail, and there is but small doubt that the Loughor will ultimately join the ranks of the Ebbw, Rhomney, Neath and other fishless streams of South Wales.”

Well, thankfully Augustus Grimble was wrong about most of that. A century later, the Loughor still sometimes ran black with coal dust, but there are veterans in the Pontardulais club who will vouch for the fact that by the 1960s it had a wonderful sewin run, although they weren’t easy to catch even by night. The Pontardulais club record for the species stands at 17 pounds. Although there are new concerns today, mainly about agricultural pollution affecting the sewin fishing, the club is highly proactive and rarely misses a chance to put pressure on Welsh politicians and officials to improve the environment. The other rivers listed by Grimble have all been restored to a large extent. In the book he described one sixth of the rivers in England and Wales as destroyed by pollution. Only in the case of the Thames and the Mersey would this be strictly true today.

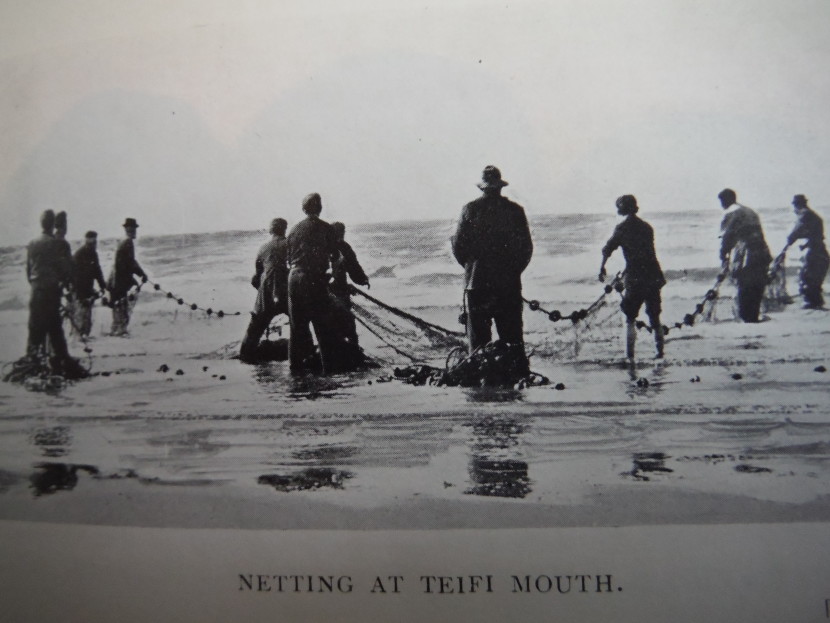

The Great Net at the mouth of the Teifi

The Great Net at the mouth of the Teifi  Brockweir

Brockweir Grimble goes on to describe the Towy and Teifi, never so badly affected by industry as the rivers of South Wales, and here he has some happier news. The Towy produced about 4,000 salmon and 6,000 sewin between rods and nets in 1875, although certainly there was conflict between anglers and netters, Grimble regarded it always as a productive river. The Teifi also had a fine reputation, although there was much dispute about the “Shot Fawr” or Great Net, which was removed from the estuary to Milford Haven in 1896. So the survey continues, to the Dovey and North Wales, eventually to Cumbria and Northumberland. I don’t have space to go into that now, but I would certainly be inclined to read the relevant section carefully should an invitation for a northern trip come my way.

Today our rivers are in trouble, as we know well, but they have been in trouble before and I feel to an extent encouraged after reading Grimble’s book. There are lessons to be learned from his examination of what happened during the last half of the 19th century. Anglers are inclined to imagine that the problems of today are the only problems there have ever been and that somehow it was always better in the past. Consider the situation Grimble encountered in this area in 1904, with the Wye in the doldrums through over-netting and many of the South Wales rivers completely wiped out, dead through industrial pollution. Taken altogether, these problems were at least as bad as those we face today, and probably worse. In the case of the Wye they were overcome in time due to local co-operation, a well-judged seasoning of diplomacy and some determined national legislation. The result, taken in merely financial terms, was that angling rents for the river went up from 1,000 pounds to 8,000 pounds in just 13 years. Salmon fishing was always about money to some extent! Another lesson, very plainly demonstrated here, is that in the case of both the Wye and the Usk it was the anglers who had the motivation and the perseverance to improve the river. It was ever thus and proved to be so later when the South Wales rivers were restored from pollution. One very obvious fiscal lesson is that commercial netting, if done efficiently and profitably and without legal checks, rapidly expands to the point when the natural resource itself diminishes or disappears. In this case, unrestrained capitalism doesn’t work. In the end, everybody loses. We should know this of course, but if you look at the recent history of marine catch quotas and sea fishing policy around Britain’s coastal waters, it becomes apparent that actually we don’t. I had been hoping that an improvement on the distinctly disastrous EU fishery policy would mean that conservation would now be given priority with a view to sustainable exploitation in the future. Instead we seem to be engaged in a wrangle with the French over whether it is we or they who are going to over-fish British waters.

Perhaps Grimble should be allowed a final word on the Usk and the Wye as he knew them compared to other British rivers: “The Tay, with its catchment basin of two thousand five hundred and ten square miles, and the Spey with its one thousand and ninety-seven square miles, have never, in proportion to their drainage area, equalled the rod takes of the Usk in its palmiest days with its small basin of only six hundred and fifty square miles; in 1872 and 1873 the rods on that river landed about 2,000 salmon in each season; in 1879 their catch was close on 3,500 fish, and I believe that the Aberdeenshire Dee, with its basin of eight hundred and twenty-four square miles, is the only river in the United Kingdom where the rod catch has exceeded that which was made in the Usk in 1879. Sad to relate, that in recent years the glories of the Usk have dwindled…But to come right up to date - 1913 – look at the wonderful improvement in the Wye, where good management has turned a poor yielding river into the very best in the United Kingdom!”

Lyepole valley in frost - AP from Wirral

Lyepole valley in frost - AP from Wirral  Springer going back

Springer going back I’m closing the newsletter early this month (24th January) as for us the final week is to be taken up with moving house. This is an operation I dread although we have done it a few times over the years. I suppose that I have grown too comfortable in the familiar place. Nermana has always travelled light and the children have flown the nest long ago but I’m afraid I have become a hoarder these days, accumulating old fishing tackle, old pictures and books and heaven knows what else. When I worked abroad it was in store, but in recent years I have happily spread my stuff around. It all has to be packed and moved now, and this when conditions for grayling fishing look just about perfect! Let’s hope we get some more grayling opportunities in February, the shortest if often the coldest month, after which 3rd March will lead us back into spring and the new seasons for trout and salmon. Is anything more delightful than to be beside the Usk on a spring day with some fly hatching? Or maybe trying for a springer on the Wye with the willow buds showing.

Tight lines!

Oliver Burch